Following the conclusion of his first and only term in Congress, Abraham Lincoln chose not to run again, but did strive for a continued role in the national political arena. As detailed in the Shrine’s letter from Lincoln to Archibald Williams in April of 1848 (Lincoln Dinner Sponsorship Acquisition, 2022), he was a strong supporter of General Zachary Taylor, the Whig nominee in the 1848 presidential campaign and hoped his support would translate to an appointment as Commissioner of the United States General Land Office. Disappointingly, the administration offered the post to Justin Butterfield, a well-respected Illinois lawyer. Lincoln remained faithful to the Whig Party.

Instead of the post he sought in the General Land Office, the Taylor administration offered Lincoln the appointment as territorial governor of the Oregon Territory. The territory, which encompassed an area including all of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming, was a Democratic stronghold, having been a destination for many Americans who traveled the Oregon Trail during the 1840s. It was acquired by the United States in 1846 as part of President Polk’s campaign to expand American holdings in North America. The territorial government was established in 1848 and was governed by Polk appointee Joseph Lane. Lane’s resignation in 1849 led to Lincoln’s prospective appointment.

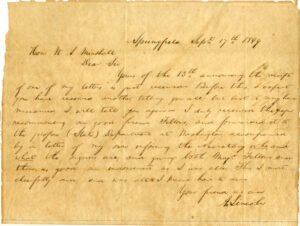

The distant post was undesirable to Lincoln, who recognized the detrimental effects it would have on his career. It is believed that his wife, Mary, also opposed the move. Lincoln skirted the appointment, recommending fellow Illinois attorney Hart Fellows to Taylor’s Secretary of State, John M. Clayton. He explained the situation in a letter to Minshall, a fellow Whig, on September 17, 1849, writing:

Dear Sir

Dear Sir

Yours of the 13th announcing the receipt of one of my letters is just received. Before this I expect you have received another telling you all but lest it may have miscarried, I will tell you again. I duly received the paper recommending our good friend, Fellows, and forwarded it to the proper (State) Department at Washington accompanied by a letter of my own informing the Secretary who and what the signers are and giving both Majr. Fellows and them as good an indorsement as I was able. This I most cheerfully did and was all I knew how to do.

Your friend as ever

A. Lincoln

Clayton did not take Lincoln’s recommendation and appointed Oregon’s acting territorial governor, John P. Gaines, to the top post. Gaines’s appointment proved to be a failure and he was removed from office in 1853. The southern portion of the territory became the state of Oregon in 1859.

He remained out of politics throughout the early 1850s, as the Whig Party declined and tempers flared over the expansion of slavery into the west. He was spurred to action by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which created two new western territories where popular sovereignty was put in place, allowing for the expansion of slavery into the west. Lincoln openly condemned the law in a well-received speech in Peoria, Illinois in October of 1854, which signaled his return to politics. He joined the newly formed Republican Party, and gained national prominence in the years that followed.

Unveiled at the 2025 Watchorn Lincoln Dinner, Lincoln’s letter to William Minshall offers an interesting sliding doors scenario. What would have happened if Lincoln had taken the appointment?

The acquisition of this manuscript was made possible by generous donors to the 2024 Watchorn Lincoln Dinner Sponsorship Fund.