By the spring of 1864, a garrison of 600 soldiers, including 262 U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery soldiers, protected the fort. District of Tennessee Commander General William T. Sherman ordered the fort abandoned in January, but his orders were disregarded, which proved to be a tragic mistake.

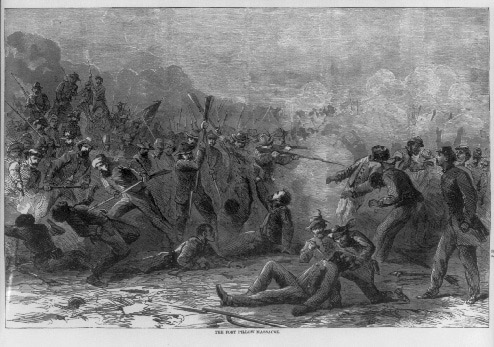

On April 12, Confederate General Nathan B. Forrest and 1,500 cavalrymen reached Fort Pillow and easily overtook the troops stationed there. Although the fort was surrendered, over 300 men, women, and children were killed. Most of the dead were African American. Confederate anger over the inclusion of black soldiers in the United States military was palpable by this point in the war and the position of rebel officials was that these men should be treated as insurrecting slaves and not be afforded the rights of prisoners of war.

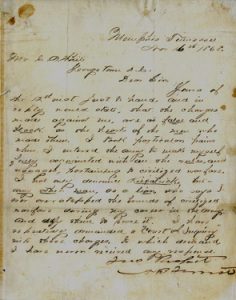

The events at Fort Pillow did not slow down Forrest’s career and within a year he was promoted to Lieutenant General. Fort Pillow remained a blight on his reputation. In this November 16, 1868 letter from the Shrine’s collections, Forrest responded to a letter from C.A. White of Georgetown, Washington, D.C. about his complicity in the Fort Pillow massacre. Forrest denied that he “ever overstepped the bounds of civilized warfare” during his military career and described the charges as “false and black as the hearts of those men who made them.” Fort Pillow remained a hot button issue between the North and South long after the end of the war.